|

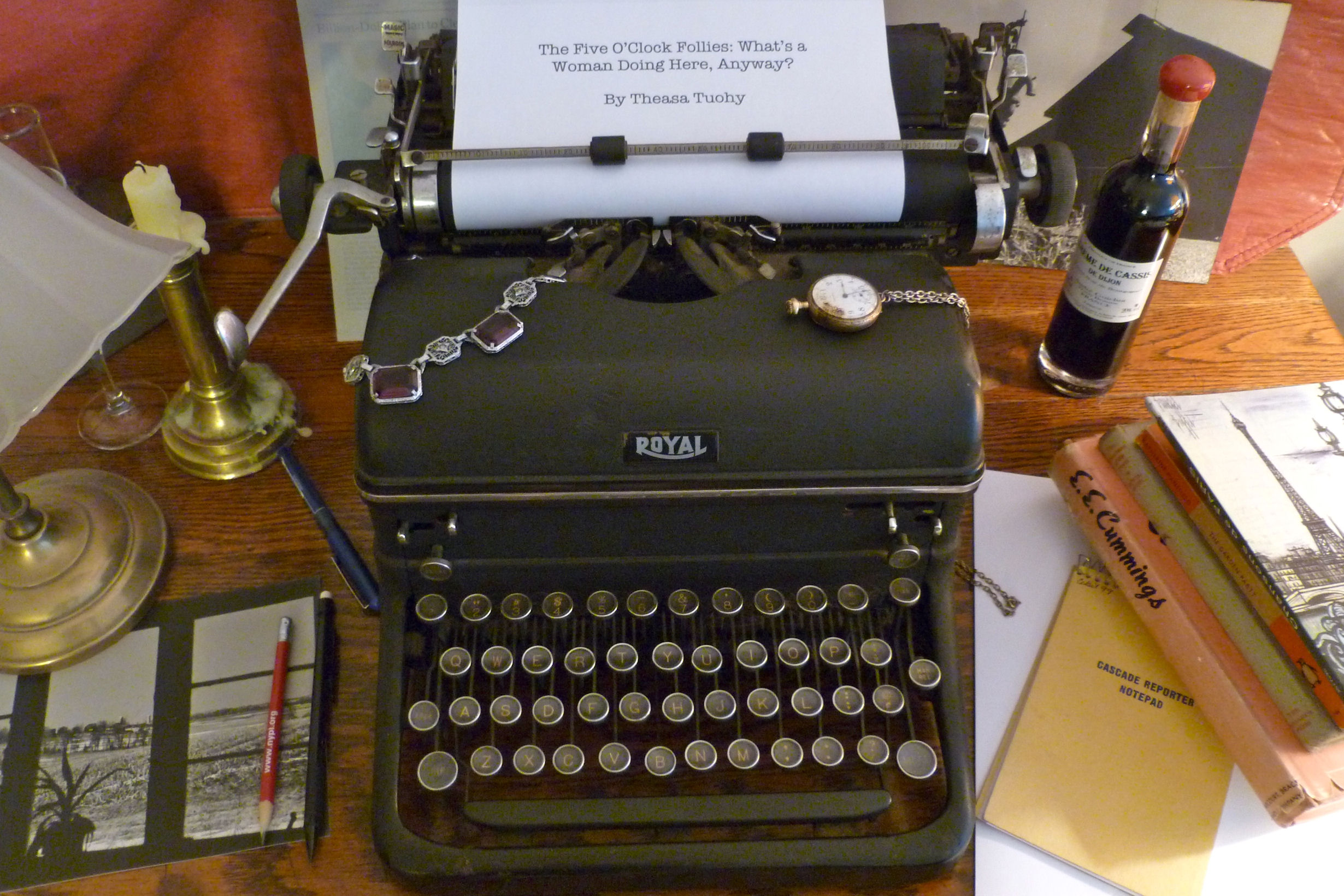

Excerpt 01 Bird Watching

It was the sounds of the camera that caught Nick’s attention. Bo Parks, his photographer for the assignment, must have spotted her as soon as she appeared in the plane doorway. From the shots Nick saw later, Parks’ camera was clicking away the moment her foot touched down on the top ramp of the metal stair rolled up to the DC-10. At the other end of the field, a little Army Huey rose straight up, its double dragonfly rotors sucking more dust and gravel into the already opaque air. But it was that urgent clicking-whirr of the Nikon that made Nick look away from the congressional delegation that had just deplaned and was moving like a mirage through the shimmering heat. Nick O’Brien’s assignment that blistering day – when Ho Chi Minh City was still called Saigon – was The Honorable Representative from Chicago. Nick had been trying to single out the politician from the rest of the pack. Swiveling in the direction of the camera, Nick saw her just as Parks let out a pent-up sigh of breath that formed the words, "What a bird!" The tall redhead moved like an oiled machine. A classier person might use a word like grace, Nick thought, but that wasn't really it. She was fluid, her back straight, her head high, but nothing rigid – she flowed. Her legs were long and slim and firm, smooth pistons, down then up, as she negotiated those steps wearing the closest thing Nick'd ever seen to high-heeled bikini shoes. Just a thin strip of leather across the back of her heel and another across her bare toes and that was it. The movement dappled the hem of her light summer dress, which was already starting to glue to her body in the sudden rush of Saigon's sludge-like heat. She clutched the brim of a giant saucer of a sunhat, and a Leica on a Swiss-embroidered strap hung over her shoulder. Parks was gyrating like a fashion snapper out of Antonioni's "Blow-Up." It was whirr-click, whirr-click, down on one knee, up again, right hip out, hip in, camera straight up, camera sideways, all in a blur of motion that would produce a score of shots in the matter of seconds it took Parks’ bird to descend the stairs. Nick's congressman was proceeding across the tarmac toward the low-slung Quonset terminal of Tan Son Nhut, and Nick had to snap his own mind back to business. Shit, he thought, the city desk back in Chicago would have his ass if he let their prey get away while he was bird-watching. He usually worked for the foreign editor, better known as Harry "the Arse" Bodowsky. But this time, the local desk needed some inane hometown comment from The Chicago Honorable on the earth-shattering significance of his junket into a war zone to assess the U.S. "effort" in Vietnam. Nick had brought Parks along to catch the political mouth in motion. He jabbed Parks with an elbow. The combat photographer was a scarecrow with a doper's ever-present, vacant grin. A London street kid, Parks had never been in a dentist's chair and his teeth were a mass of rotting stumps. Limp, greasy hair hung to his skinny shoulders except for a shock of cornsilk that stood straight up over his right eye. "Get the lead out, Limey," Nick ordered as he jerked his head toward the terminal and then headed in that direction at a trot. 02 And All That Jazz She stepped from the refrigerated cool of the Pan Am interior onto the sizzling metal ramp that burned through the thin soles of her high-heeled sandals. Her eyes smarted in the haze, squinting into the blast furnace of sunlight that was Saigon. The heat literally took her breath away. Stomach knots rose up to greet the stagnant air blasting its way down, a collision course that made her heart race, then thud, then flip-flop. What an embarrassing place for a coronary, she thought, right here at the top of the stair. The Quonset terminal flashed fast forward, out of control, a photographer on the tarmac took flight, sailing past, then reversed himself and flew backwards like a Mexican road runner in a stop action shot from a childhood cartoon. Dizzy, she shook her head and tried to clear jet lag and yesterday from her brain as she started down the stairs to her new life. She had come out of the bright sunlight of Broadway less than 36 hours before, down those steps in her high heels, into darkness and the smell of marijuana that hung sweet in the thick cabaret air. The horns of the yellow streams of taxis feeding into New York’s Times Square were muting behind her as a soft, high screech hit like a rush of adrenaline. Coltrane was playing! She hesitated, trying to adjust her eyes to the blue haze layered over the dim light. Coltrane, that sax that could wail like an agonized bird. Had Jackson known The Trane was playing when he picked this place to meet to say goodbye? She took a deep breath to calm herself, but all she got was a lungful of smoke – it hadn't been an easy day. Stepping off that elevator on the fourth floor of The Associated Press, asking for the foreign editor, hearing him warn her Saigon was a mess, nothing would be easy from here on. That was a big move in her life. This was a little one, just a few stairs down into one of the last joints left on 52nd Street, legendary land of jazz, a trip back into her past. But only for the evening, just for a little while. Then off to work, the one thing you could count on. No family second-guessing, no betrayals. An enemy on the battlefield, straightforward as that. Off to the land of Vietnam with a camera handed her by the editor, no strings attached. Just send them war pictures, and they’d pay $15 to $25 for each usable shot. You make your own way. No strings, how nice. Nothing to tie, nothing to bind. And no one to care. The man taking admissions at the bottom of the stairs said Jackson had paid and pointed her way to his table. Through the haze, she could make out the rapture in his posture, tilted as his long bulky body was toward the musicians on the slightly raised stage. She thought he wouldn't notice, wouldn’t see her coming, but he did. Yet there was no sign of acknowledgment as he watched her move through the red-checkered tablecloths, making her way toward him, the house-painter's son in the undertaker's suit, with no expression on his face. "Hi, my lady." He didn't smile or get up. He didn't straighten from his slouch as she bent down to brush her lips against his cheek. "It's been four years, Jackson," she said. "You act like it was yesterday." "I know, my lady," he said. "Too cool to be forgotten," she said. He looked surprised. "Who, you or me?" he asked with a grin, the first emotion to touch his angular, pockmarked face since she'd walked in. "I'm not cool, Jackson, I never was. The gremlins are always there." "Au contraire. You're the metaphor for cool, lady." Back at square one. Why was she always the one accused of being distant? "I got it," she said, changing the subject. She patted the Leica, putting it on the tiny table between them. "This is my passport to Vietnam." "Peter?" he asked. "It's over," she said. "Oh?" the question was as light as the touch of his horn blower's fingers, which he was playing across the ridges of her newly won camera. "I wasn't much of a wife." "I thought he liked to do the cooking.” He grinned his wicked grin, and bent forward to his absent horn, his slicked-back shoe-polish hair falling forward on each side of his 1940s center part. He played a phantom riff on his imaginary sax as he duplicated the forward sway of the on-stage Coltrane. Only the song he mouthed to her across the drinks on the tiny table was different. "But then, again, it's not for me to say." "I guess no one wants to carry someone else forever," she said, moving to pick up her Scotch to avoid the intensity of his stare. "You get around without much help, Valentine. But I would've carried you, if that's what you want." Again she was reading his lips, their faces so close, the music so loud, in the small space. "You weren't taking either of us any place, Jackson. We parted over that long before I met Peter. We had no home life, remember? Booze and drugs and one-night stands." "I wasn't drugged." "Everyone else was." "So? That wasn't me. I'm a musician, for Christ sake. That's the way I pay my freight. And don't lay on any of that old crap. I earn my bread, good bread." She smiled to herself. Peter had made bread, too. Real bread in the kitchen, punching down dough, his hands floured, white handprints on his big canvas apron. A husband who had created a nest, who was a shelter. "Jacks, I don't know what's wrong with me," she said. "I do. You're a class act, my Valentine, but you'll never outgrow Doctor Mom’s expectations. Always one more river to cross." His horn blower's cheeks puffed air through his nose. "Harvard and all that, you know." "You haven't changed," she said with a grin, hearing Coltrane on the stage and Coltrane in her mind, the first time she’d heard "Ole,'' that familiar opening vibration: plunk, plunk, plunk of the bass strings and then the straining to hear, worrying the record player wasn't working quite right, the first off-stage, nearly inaudible notes from the arriving piano. Coltrane's sax so soprano it sounded like a flute, a trilling Arabic bird, then there really was a flute. Where did one end and the other begin? Maybe there really was a bird. A down-home country viola, fiddlestick backwards, wood on wood, where was the right key? Atonal, yes, but wow she'd grooved on it. Jackson had been amazed, and impressed, when he'd noticed her fascination with the record at an off-campus party in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. "Very sophisticated taste,'' he'd said. For someone who knew nothing about jazz, he'd left unsaid. But modern jazz was the cutting edge. Few knew it, much less understood. It was exotic, spelled danger. When someone in her high school class had gotten busted on a pot charge just before graduation, most of the kids didn't know what marijuana was. "What happened?" they had whispered, gathered in clusters around their hall lockers. It was the jazz, they said, he played the trumpet, fell in with THOSE MUSICIANS, the ones who played around midnight, in dingy basement clubs, their heads poking through the circles of smoke like Washington out of Mount Rushmore. "Everyone else was into Elvis,'' she said out loud to Jackson, lost in his own reverie of "A Love Supreme" moaning out of Coltrane's horn on the stage. "Yeah," he said, "you always were out of step. Too bad you can't live with yourself that way." "Too bad," she said. Da da deda da da, he tapped flatfooted like a drummer, his black, no-nonsense, clergyman's shoe, marking the atonal passage from the wailing horn, a pedal back and forth, slapping the floor with his giant's foot. "I got a pad in the Village. Can you stay in town for a few days,” he paused, “with me?" he asked, still looking at the stage. "I can't, Jackson. I have to go. I wanted to say goodbye." "In case you get killed?" "I just want to get good at something, have something to show for myself,” she said, her voice coming out too shrill, stuck high in her throat. "But no one thinks a woman should cover a war. There's so much in the way.” "I wasn't." "Yeah, you were always off at some gig." "Doing my work, while you were doing your work. One of these years you're gonna have to make up your mind, Valentine, do you want yourself, or do you want all this togetherness horseshit." She shook her head to clear yesterday from her mind as she descended the stairs into the Saigon heat.

|

||||