|

| ||

|

|

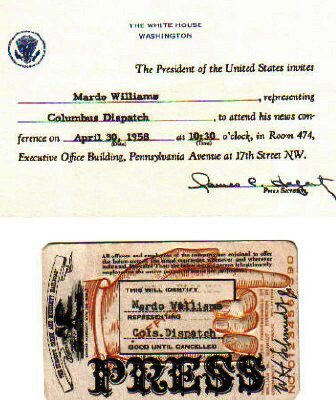

My Accidental Career (from Ohio Connections) Photos courtesy Jerri Williams Lawrence and Kay Williams, Mardo's daughters "Wanted: young man interested in meeting people and writing. No experience necessary." I am an old-time newspaperman who remembers too well the noisy, smoke-filled newsrooms of the past and the crotchety news editors who called the shots.

I am an old-time newspaperman who remembers too well the noisy, smoke-filled newsrooms of the past and the crotchety news editors who called the shots.

I began my 44-year reporting career in 1927 by accident-because of an aversion to house-cleaning. Recently unemployed, I had been helping my wife wash the kitchen walls when an ad on the front page of the Kenton, Ohio News-Republican caught my eye: "Wanted: young man interested in meeting people and writing. No experience necessary." I applied immediately and was hired at age 21, an ex-machine shop employee with only a high school education. I started at $8 per week-as the only reporter Three weeks later, in a hurry to meet the pressroom deadline, I turned in a story reporting the "assignation" of court cases. The editor-publisher, almost a foot taller than I, brandished a proof of the story and, with a sly smile, demanded to know how that was going to be accomplished. Fearful I was about to lose a job that already was the most interesting I had ever held, I spelled assignment, the word I had meant to use. Then I listened to a 15-minute lecture about the necessity of getting every fact right and every word spelled correctly. Back then, no one had time to coach the reporter. If he didn't know how to spell, he consulted Webster's Unabridged Dictionary, which occupied a pedestal in the midst of the action. If he used the wrong word, he received a lecture. If he didn't know how to write the facts, concisely and interestingly, he was told to get a job as a copy boy and begin learning the trade.  I started at $8 per week-as the only reporter. In those days, reporters on small non-union newspapers were truly jacks-of-all-trades. I did the leg work. I read records. I covered meetings, writing the details in longhand on a pad, then pounded out the stories on my trusty Underwood typewriter. Back at the office, I read and corrected galleys of type, assembled hand-set headlines on the Ludlow machine when the five-man composing room crew was busy. I even delivered newspapers to customers when the carrier missed them--if I was working late at the office.

I started at $8 per week-as the only reporter. In those days, reporters on small non-union newspapers were truly jacks-of-all-trades. I did the leg work. I read records. I covered meetings, writing the details in longhand on a pad, then pounded out the stories on my trusty Underwood typewriter. Back at the office, I read and corrected galleys of type, assembled hand-set headlines on the Ludlow machine when the five-man composing room crew was busy. I even delivered newspapers to customers when the carrier missed them--if I was working late at the office.

The flat-bed press had to be stopped every few minutes Each day as press time approached, the foreman and a helper wrestled the 150-pound forms, filled with metal type, to the basement via dollies and a dumbwaiter. The forms were locked in place on the flatbed press, which could print as many as 12 pages at a time. The press had to be stopped every few minutes to oil a bearing or coat the rollers with another application of ink. When the newsprint ripped, the run was stopped and the two dangling ends were pasted together. It took almost two hours to print and fold the 5,000 daily papers and deliver them to carriers and post office. I covered all breaking news stories, including an interview with Amelia Earhart the year before her ill-fated flight For the next 19 years I received an intensive education in the newsroom of this small Ohio daily. My salary increased as I became more valuable. During the Great Depression, it climbed to $16 per week-most of it in scrip, chits good for merchandise at the stores that advertised in the newspaper. I added to income by submitting stories to as many as five metropolitan dailies and one wire service, earning more as a stringer than as a News Republican employee. When my father-in-law was elected Hardin County sheriff in 1929, he appointed my wife matron of the jail. I moved in, too, and had first dibs on all the breaking news stories in the area. I covered a train wreck nearby, which killed l4; an automobile-truck crash in which five prominent Kenton women burned to death; and a host of events that included the arrest of rum runners taking moonshine whiskey from the hills of Kentucky to Toledo and Detroit, an interview with Amelia Earhart the year before her ill-fated flight, and the death of a budding movie star on the icy highway west of Kenton. I never attempted to interview Jimmy Willis, the killer of my uncle When the attempted unionizing of Scioto Marsh onion field workers turned violent and a barn was burned, I was there, both as special deputy to maintain order and as reporter on top of the developing story (billed as the first attempt by organizers to unionize the nation's farm laborers).  However, I never attempted to interview Jimmy Willis, the killer of my uncle, Roy Ansley, although he occupied a cell in the jail where my wife and I resided. Willis, recently released from the reformatory, was found guilty of breaking into Ansley's home and shooting him while they struggled for the gun.

However, I never attempted to interview Jimmy Willis, the killer of my uncle, Roy Ansley, although he occupied a cell in the jail where my wife and I resided. Willis, recently released from the reformatory, was found guilty of breaking into Ansley's home and shooting him while they struggled for the gun.

My publisher banned all interviews of the Willis family, just as he had ruled "no" on interviews in the fiery deaths of five Kenton women. It was considered an unwarranted invasion of privacy. As a newsman from the old days, I dislike the "in your face" tactics of reporters today who intrude on a family's grief to get a tearful picture. Television journalists seem the worst offenders. My publisher had other, similar "old fashioned" rules. He didn't care if the paper was politically correct, but he demanded the story be factually correct, both sides fairly presented with no editorial observation by the writer. Rape was called criminal assault, and the word gutted was banned in his family newspaper. The Columbus Dispatch lured me away with the promise of $60 a week  I was 36 years old when World War II struck. While waiting to be drafted, I took a 3 PM to 11 PM job at the Lima (Ohio) Tank Depot, and continued part-time work at the newspaper. I helped prepare tanks for service on the European, Russian, and African fronts, working double shifts when an ally ordered emergency equipment. The day after Japan capitulated on August 14, 1945, I lost my job.

I was 36 years old when World War II struck. While waiting to be drafted, I took a 3 PM to 11 PM job at the Lima (Ohio) Tank Depot, and continued part-time work at the newspaper. I helped prepare tanks for service on the European, Russian, and African fronts, working double shifts when an ally ordered emergency equipment. The day after Japan capitulated on August 14, 1945, I lost my job.

Before the ink was dry on my last defense check, the Columbus Dispatch lured me away from the News Republican with the promise of $60 a week as a copy editor, as much money as I had been making at the Lima Tank. I edited another's stories, I wrote headlines, I watched for errors in fact and possibility of libel. To me, the copy editor held a coveted position. He was the expert who could take the words of another writer and make his message more concise, more interesting, even exciting. I thought the editor had chosen me for this role because of my 19 years of writing about every subject on a small newspaper. Then I learned that most new staff members were introduced to the Dispatch the same way. The copy desk was a proving ground.

I wrote a daily column for the last 16 years of my Dispatch career. The writing didn't have quite the thrill I experienced as the only reporter on the little Kenton paper, but I tried to make the business news interesting and easy to understand.  I fought against the temptation to use business-financial jargon, keeping in mind the words of an executive of the automobile dealers association who cautioned me, "Don't change your style." The best compliment I ever received came second hand. A woman sales clerk at Columbus' biggest department store told my wife the first thing she searched for in The Dispatch was my column, because she found it not only interesting but written in language she could understand.

I fought against the temptation to use business-financial jargon, keeping in mind the words of an executive of the automobile dealers association who cautioned me, "Don't change your style." The best compliment I ever received came second hand. A woman sales clerk at Columbus' biggest department store told my wife the first thing she searched for in The Dispatch was my column, because she found it not only interesting but written in language she could understand.

Sweeping changes, good and bad By the mid-1950s, reporters at the Columbus Dispatch had started inserting their own views about the meaning of the facts. They did more interviewing. Some carried tape recorders, especially those who were assigned to investigate potential wrongdoing in public offices. Public relations persons sent well-written stories about industrial, financial, commercial, health, or educational clients. In the 1960s, management relaxed its ban on use of "rape," "gutted," and other words and topics that had been considered objectionable in a family newspaper. Reporters competed for bylines on feature stories and for roles as columnists, or editors in charge of special sections and departments. Typesetting became faster; engraving processes were simplified; cameras were improved. Photographers were on the verge of being able to take a photo at the scene and submit it directly from the camera to the engraving department over telephone wires.

We didn't "color" our interviews as some reporters do today  Reporting was more personal when I started. You met the principals, not a public relations spokesman who handed you the story as a press release. I believe such people contribute to the laziness of reporters. In the 30s and 40s, if we didn't get both sides of the story, we could always write that the company owner or executive, the union representative or politician had "no comment." There was no "special interest middleman." Reporting was more personal when I started. You met the principals, not a public relations spokesman who handed you the story as a press release. I believe such people contribute to the laziness of reporters. In the 30s and 40s, if we didn't get both sides of the story, we could always write that the company owner or executive, the union representative or politician had "no comment." There was no "special interest middleman."

We didn't "color" our interviews, as some reporters do today. We got the facts, quoted the principals, and never made observations of our own. We left that to the opposition leaders-if there were any. Newspaper reporting continues to be the most challenging and fulfilling career in the world

Newspapering is now vastly different from when I started. If I stopped by The Dispatch today, I'd need clearance by the security guards. I'd miss the old camaraderie, the clatter of typewriters, the jangle of ringing phones and the smoke-filled confusion. But, to me, newspaper reporting continues to be the most interesting, the most challenging and the most fulfilling career in the world. It will always attract professionally curious young men and women with its promise of being "the first to know, the first to tell." |

| ||||||||||

| Order · About The Author · About The Book · Excerpt · Critics Corner · Readers Speak · Contact Us · Home | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

© 1999-2025 Calliope Press All rights reserved. For more information call 1-212-564-5068. |